Researchers build a portable desalination unit that generates clear, clean drinking water without the need for filters or high-pressure pumps.

MIT researchers have developed a portable desalination unit, weighing less than 10 kilograms (22 pounds), that can remove particles and salts to generate fresh drinking water.

The device, which is about the size of a suitcase, needs less power to operate than a cell phone charger. It can also be driven by a small, portable solar panel, which can be purchased online for around $50. It automatically generates drinking water that exceeds World Health Organization (WHO) quality standards. The technology is packaged into a user-friendly device that runs with the push of a single button.

Unlike other portable desalination devices that require water to pass through filters, this unit utilizes electrical power to remove particles from drinking water. Eliminating the need for replacement filters significantly reduces the long-term maintenance requirements.

This could enable the unit to be deployed in remote and severely resource-limited areas, such as communities on small islands or aboard seafaring cargo ships. It could also be used to aid refugees fleeing natural disasters or by soldiers carrying out long-term military operations.

“This is really the culmination of a 10-year journey that I and my group have been on. We worked for years on the physics behind individual desalination processes, but pushing all those advances into a box, building a system, and demonstrating it in the ocean, that was a really meaningful and rewarding experience for me,” says senior author Jongyoon Han, a professor of electrical engineering and computer science and of biological engineering, and a member of the Research Laboratory of Electronics (RLE).

Commercially available portable desalination units typically require high-pressure pumps to push water through filters, which are very difficult to miniaturize without compromising the energy-efficiency of the device, explains Yoon.

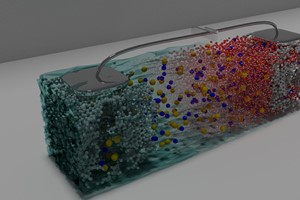

Instead, their unit relies on a technique called ion concentration polarization (ICP), which was pioneered by Han’s group more than 10 years ago. Rather than filtering water, the ICP process applies an electrical field to membranes placed above and below a channel of water. The membranes repel positively or negatively charged particles — including salt molecules, bacteria, and viruses — as they flow past. The charged particles are funneled into a second stream of water that is eventually discharged.

The process removes both dissolved and suspended solids, allowing clean water to pass through the channel. Since it only requires a low-pressure pump, ICP uses less energy than other techniques.

They shrunk and stacked the ICP and electrodialysis modules to improve their energy efficiency and enable them to fit inside a portable device. The researchers designed the device for nonexperts, with just one button to launch the automatic desalination and purification process. Once the salinity level and the number of particles decrease to specific thresholds, the device notifies the user that the water is drinkable.

The researchers also created a smartphone app that can control the unit wirelessly and report real-time data on power consumption and water salinity.